Dispatch 5: Brute Difficulty

3rd August 2012

Laura de Steur discusses the ADCP with Dan Torres and Lena Schulze |

Laura de Steur's Orange Top Float |

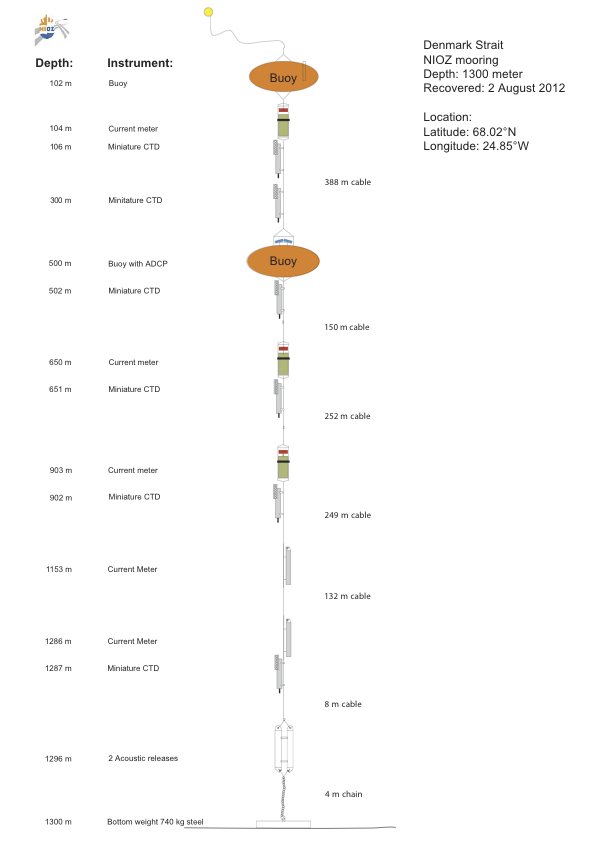

The top float must remain 100 meters beneath the surface to shield it from fishing trawlers, ship traffic, and passing icebergs. But those upper 100 meters are an important part of the water column; they must be measured. That’s where the ADCP comes in. You’ll have noticed how the audible pitch of a fire-engine siren or locomotive changes as it approaches and passes, the so-called Doppler shift. The upward-looking ADCP mounted on the top float shoots pulses of sound waves toward the surface which, when they encounter particles such as sediment and plankton drifting with the current, bounce back at a slightly but measurably different frequency. From that difference you can calculate the velocity of flow. Another ADCP mounted in the JCR’s hull pings the water throughout the cruise. When you factor out her speed and heading, you have current velocity. However, ocean currents vary widely in velocity over time, so while the shipboard ADCP is useful, it cannot substitute for those mounted on moorings, which typically remain in the water collecting data for a year and more. Also our shipboard ADCP aboard this ship is limited in range to about 400 meters.

“Oceanography is a young science, because of the brute difficulty of measuring the ocean.” - Carl Wunsch

You may well be asking, as do most first-time observers, “Wait, if this top float is anchored some 100 meters beneath the surface, how do they retrieve it?” Another sonar-related device—the acoustic release—is shackled just above the anchor. When the ship arrives at the mooring position (known thanks to GPS, which revolutionized oceanography as thoroughly as it did navigation), technicians lower a hydrophone that “talks” to the release, saying, essentially, “wake up.” The release responds in code, “I’m here and ready for instructions.” The tech then sends instructions to release, and a stout set of jaws open, allowing the mooring, minus the anchor, to float to the surface. At least that’s the way it’s supposed to happen. It doesn’t always. Sometimes the device wakes up as instructed, but refuses to release. Sometimes it remains mute. In either case, all that expensive gear and the still more valuable data is lost. When you put instruments in the water, you no longer own them; the ocean does. It may or may not give it back. Pros like those aboard JCR expect to lose stuff; it’s happened to all of them before, and it will happen again. But so far in the mooring recovery process, so good.

Hedinn Valdimarsson, Steingrimur Jonsson and Kjetil Vage |